Bad news if you want to move to the moon or Mars: housing is a little hard to come by. Luckily, NASA (as always) is thinking ahead and just showed off a self-assembling robotic structure that just might be a critical part of off-planet travel.

Published today in Science Robotics, the paper from NASA’s Ames Research Center describes the creation and testing of what they call “self-reprogrammable mechanical metamaterials,” which is a very precise way of describing a building that constructs itself. The inevitable acronym for this is “Automated Reconfigurable Mission Adaptive Digital Assembly Systems” or ARMADAS.

“We think this type of fabrication technology can serve many very general applications,” lead author Christine Gregg told TechCrunch. “In the near future, the strong autonomy and lightweight structures of our approach greatly benefit applications in harsh environments such as the lunar surface or space. This includes the construction of communication towers and shelters on the lunar surface, which will be needed before the astronauts arrive, as well as structures in orbit, such as arms and antennas.”

The basic idea of the self-constructing structure lies in an intelligent synergy between the building material – cubic octahedral frameworks called voxels – and the two types of robots that assemble them.

One type of robot walks along the surface on two legs, seemingly inspired by the kinesin transport molecules of our own biology, carrying a voxel like a backpack. When this is fitted, a fixing robot that lives inside the frame itself like a worm slides in and tightens the reversible tie-down points. Neither needs a powerful detection system, and the way they work means high accuracy isn’t required either.

You can see a pair of walkers and a mounting worm in most of the images in this post. And here’s a transport walker delivering a voxel to a placement walker, with the clipper bot lurking underneath waiting to go and lock the frame into place.

Two robots exchange a building block while a third waits below to attach it to the grid. Image Credits: NASA

The shape of the pieces allows them to be attached at various angles while maintaining the good strength of the structure. You probably wouldn’t want to store rocks on top of a dome made of this stuff, but it would be great as a base to add insulation and waterproofing to create a dwelling.

“We believe this type of construction is particularly well-suited for long-duration and/or very large infrastructure, including habitats, instruments, or any other infrastructure in orbit or on the lunar surface (utility towers, vehicle landing facilities),” said co- author Kenneth Chung. “For us, structures and all robotic systems are resources that can be optimized in space and time. It seems like there will always be situations where the optimal thing is to just leave the structure in place (and maybe visit it to inspect it with a robot periodically), so that’s where we started.”

The pieces themselves could also be fabricated on site, Gregg noted:

“Voxels can be made from many different materials and manufacturing processes. Ultimately, for space applications, we would like to make voxels from materials found in situ on the moon or other planetary bodies.”

Of course, these videos of robots at work are highly sped up, but unlike working in a factory or on a sidewalk, speed isn’t necessarily of the essence when it comes to building things in space or on the surface of another planet.

“Our robots can run faster than this paper shows, but we didn’t think it was critical to the primary goals to make them do that. Essentially, the way to make this system work faster is to use more robots,” Cheung said. “The overall strategy for scalability (speed, size) is to be able to drive scale complexity in algorithms, for design and programming as well as for debugging and performing repairs.”

The lab-developed robots took 256 voxels and assembled them into a walkable shelter structure during a total of 4.2 working days. Here’s what the beginning of this looked like (again, nowhere in real time):

Image Credits: NASA

If we sent them to Mars or the moon a year before a crew, they could build a dozen such structures twice the size with time to spare. Or maybe they could stick the necessary lining on the outside afterwards and seal it – that’s probably beyond the scope of today’s published work, but an obvious next step.

Although the robots are tethered to this laboratory environment, they are designed with battery operation or field power in mind. The connector bot is already battery-powered, and researchers are looking at ways to keep the walkers charged between or even during operations.

“We envision robots being able to autonomously recharge at power stations or even transmit power wirelessly. As you mentioned, power could also be routed through the structure itself, which can be useful for powering the structure as well as powering the robots,” Greg said.

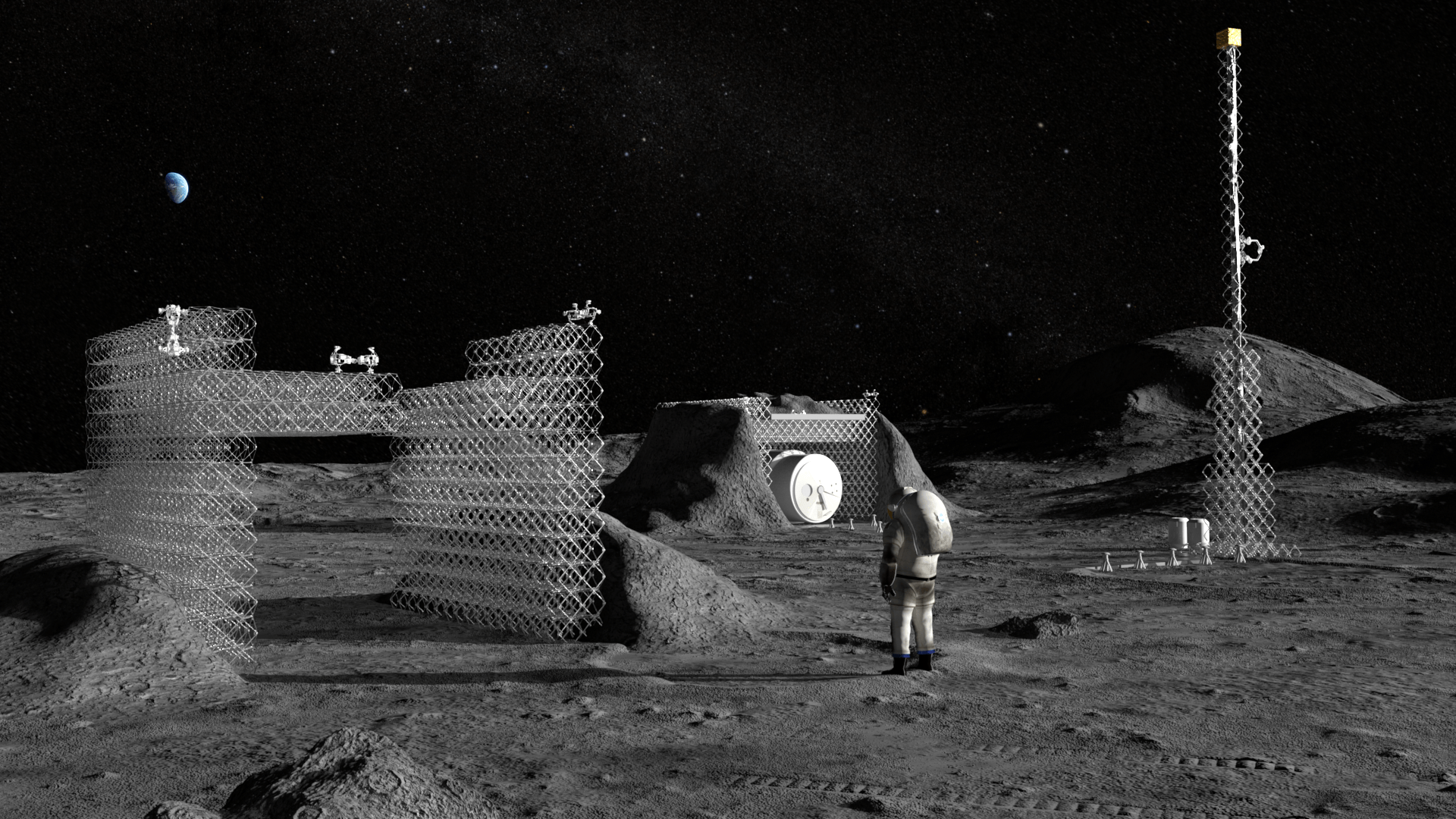

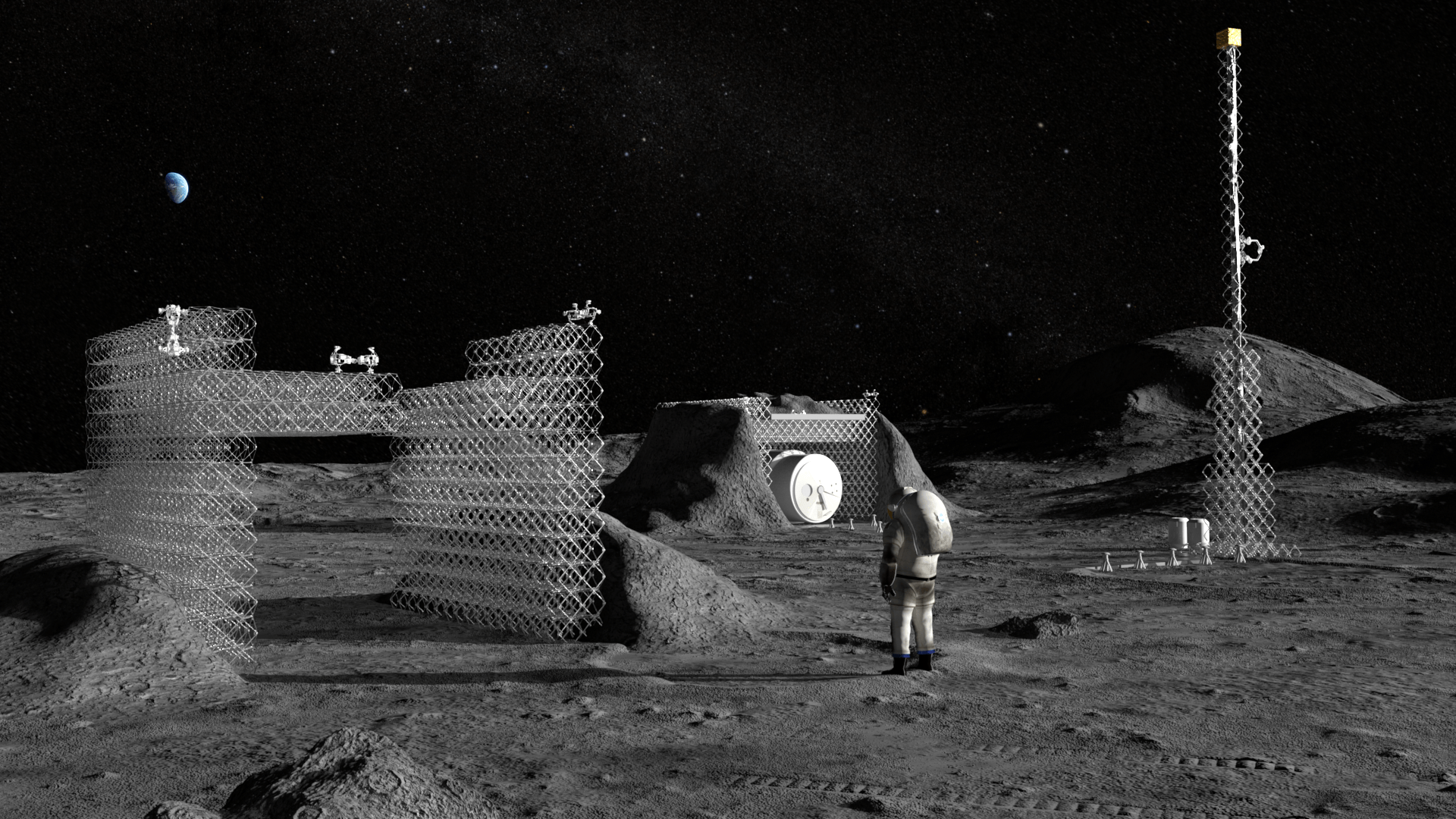

Conceptual illustration of ARMADAS building under astronaut supervision. Image Credits: NASA

Versions of the robot have already flown into space and done work in microgravity, so don’t worry on that score. And there is nothing in principle to prevent them from working at non-terrestrial gravities such as the moon. That said, this is just the beginning – like revealing the existence of 2x4s and nails. There’s more on the possibilities and conceptual renderings of what they could create, in this NASA news post.

“The next versions of our robots for the laboratory environment will be faster and more reliable, based on our lessons from the first versions. We are very interested in understanding how different types of building blocks can be incorporated into structures to provide functional equipment,” Gregg said.

Likewise, research will continue into structures that use swarms of robots, not just a handful. A crude shelter can last two walkers four days, but something 10 times larger can last 100 times longer. But many hands – especially robotic ones – make the light effect.