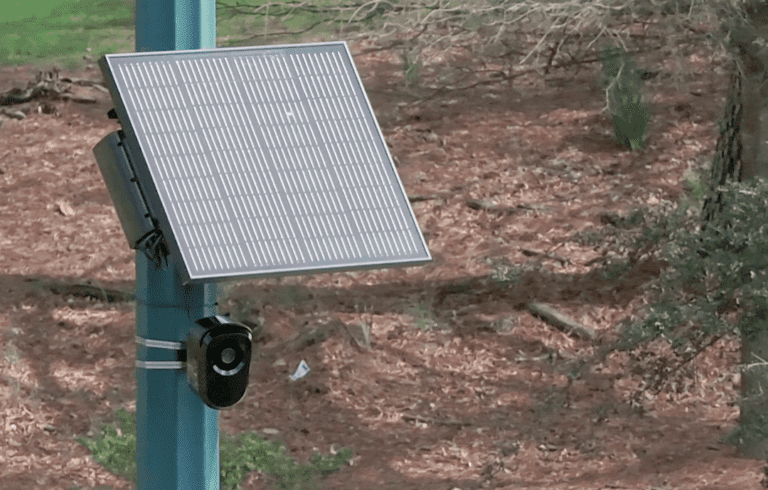

Flock Safety is a multi-billion dollar startup that has eyes everywhere. Starting Wednesday, with the company’s new Solar Condor cameras, those eyes are powered by solar energy and use 5G wireless networks to make them easier to install.

Adding solar power to the mix means the company’s mission to cover the country with cameras just got a whole lot easier. The company says the Condor camera system is powered by “advanced AI and ML that continuously learns with cutting-edge video analytics” to adapt to changing needs and that “With solar deployment, Condor cameras can be placed anywhere.”

However, the company has drawn resistance and scrutiny from some privacy advocates, including the ACLU.

“The company has so far focused on selling automatic license plate recognition (ALPR) cameras,” the ACLU wrote in a 2022 report. finding ethical problems with networked tracking cars as they traveled. The ACLU has advised communities to dispose of Flock Safety products. Last year, he published a guide to how to slow down mass surveillance with the company’s products.

Flock Safety is an extremely well-funded startup. PitchBook reports that the company has raised more than $680 million to date, at a valuation close to $5 billion, including a16z’s American Dynamism fund, which has used money in law and order products such as police dronescorporate legal subpoena responseautonomous water protection drones and 911 call response systems.

It also claims to be effective in helping law enforcement identify criminals: the company says that 10% of reported crimes in the US solved using its technology.

The problem is that Flock Safety doesn’t exactly have the best track record for accuracy. In New Mexico, police mistakenly treated some drivers as suspected violent criminals and held them at gunpoint after the company’s cameras misread license plates. according to KOAT Action News. The company was also reportedly sued when an Ohio The man was allegedly wrongly identified as a human trafficking suspect. The lawsuit was he was later fired. The company has generally exercised control over the privacy risks with national shared databases.

A report from the Science, Technology, and Public Policy program at the University of Michigan concludes that “Even when ALPRs work as intended, the vast majority of images captured are not associated with any criminal activity,” and therein lies the problem: Filming all Time necessarily brings with it some privacy challenges.

“Many tens of thousands” of cameras

When you cover the country with cameras, it stands to reason that the frequency of times a single car is spotted increases. About a decade ago, the Supreme Court ruled that tracking a car using a GPS tracker for more than 28 days violates the Fourth Amendment’s rule against unreasonable search and seizure.

It becomes a philosophical question at this point: How many license plate recognition data points do you need before a networked array of cameras can track a vehicle with similar resolution to GPS? I posed this question to Chief Strategist at Flock Safety, Bailey Quintrell.

“A GPS tracker essentially has your location, live — every second or so, depending on how it’s set up,” Quintrell told TechCrunch after confirming that there are “several tens of thousands” of the company’s cameras in operation. “With our cameras, they’re installed in plain sight, clearly there. Maybe that sounds like a lot. But on a national scale, it’s actually not that many.”

This may be true nationally, but the density may be much higher in some communities. In Oakland, California, where I live, Governor Newsom recently announced a plan to blanket the city with cameras.

“By installing this network of 480 high-tech cameras, we are equipping law enforcement with the tools they need to effectively combat criminal activity and hold perpetrators accountable,” Newsom said. in a statement in March of this year.

However, Quintrell claims that even high-density camera coverage is a huge issue.

“So it’s a very different level of information than, say, a GPS tracker,” Quintrell says, refuting my suggestion that maybe cameras could be comparable to GPS if the density gets high enough. “I think the bottom line [where we know where everyone is at all times] it is quite far. There are many miles of roads, many intersections, many parking lots, many roads. I don’t know the numbers there, but it’s a lot more than the number of cameras we’ve sold.”

True, perhaps, but the company boasts that it’s trusted by more than 5,000 communities across the country, and finally, with its investors not breathing, the company shows little inclination to slow its spread.

Data Retention

One of the big challenges with camera technology is how long cameras store footage and data. Flock recommends storing data for one month by default.

“[Data] it’s stored on the device for 30 days and then it’s live or you can download it from the device,” confirms Quintrell.

This data retention policy is one of the things the ACLU specifically takes issue with, arguing that a 72-hour policy should be plenty for videos, but the organization is pushing for the data to be “deleted and destroyed by Flock no more from three minutes after photos or data are first recorded.”

The ears and eyes of the police department

We live in a complex world where many police departments struggle to recruit the staff they need, and where a degree of video surveillance or AI-enhanced policing can help fill the gap. I asked Flock’s chief strategy officer what he’s most excited about.

“The most exciting thing? There are many places where there is a lot of crime and where there is no way to capture objective evidence (…) Law enforcement has a harder time recruiting people. So hiring is down and retail crime has continued to skyrocket, which ends up costing us all. It just ends up driving the price of everything up,” says Quintrell.

“If you’re a police department, it’s so hard to recruit people who are willing to wear a badge and do a really hard job. Just let us help you get the evidence to the places you need it, whether it’s junctions or parks or a customer in your business: you’re just trying to keep your stock from walking out the door without getting paid. [Solar Condor] it turns a really complicated, expensive construction project into something simple. We just need a few hours of sunlight and a place to put a pole and we can help you solve this problem.”

It’s hard to argue with the fact that it’s hard to hire cops these days, and I have no doubt that with solar power, the logistical issue of ubiquitous camera coverage has become much easier. But with great (solar) power comes great responsibility—and the question is whether a network of cameras run by a private, for-profit company has the right level of oversight and accountability needed to make up the shortfall.

UPDATE: The story has been updated to reflect that one of the lawsuits was later dismissed.