Railway business company Astroscale revealed new details about its approach to refueling satellites in space as part of a $25.5 million project exploring the idea with the Space Force. Their solution is a bit like a AAA truck traveling at 25,000 MPH.

The idea of repairing and repairing in orbit is attractive to anyone who doesn’t want to see a $100 million investment literally go up in flames. Many satellites are perfectly functional after years in space, but simply do not have the fuel to stay safely at their designated altitude and orbit and must be allowed to drift away.

You could build another $100 million satellite—or perhaps, as companies like Astroscale and OrbitFab have suggested, you could spend a tenth of that to make a gas flow from the surface into geosynchronous orbit.

Of course, most satellites aren’t designed for refueling, but that could easily change — even if how to do that is an open question. Astroscale won a Space Force contract last summer to explore the possibility in orbit, and the company has just released how it plans to do so.

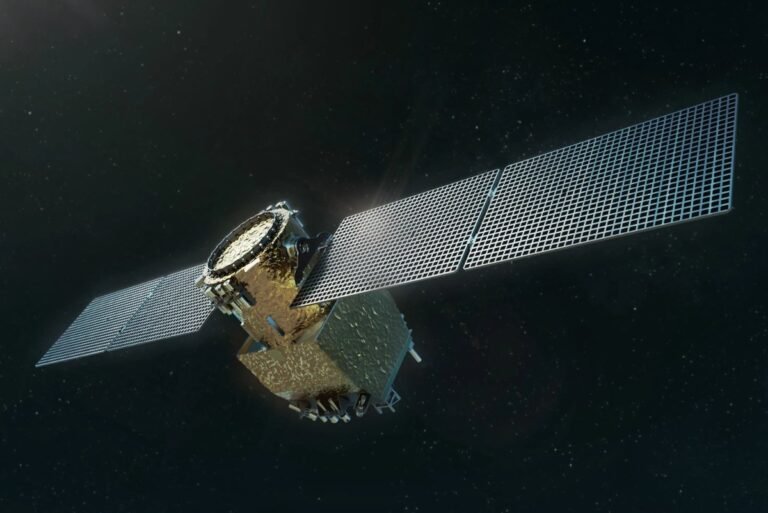

The Astroscale Prototype Servicer for Refueling, or APS-R, is a small (funnily enough, “the size of a gas pump”) satellite that will go up to GEO – about 300km up – and then come down to a “customer ready” with the right refueling port. (This client is still “eg” on the chart, so there’s no official plan yet.)

After refueling, APS-R will back down and conduct an inspection of the client satellite, looking for any fuel leaks or other issues its operators may want to check. It then climbs back up to GEO+ and encounters a Defense Innovation Unit RAPIDS fuel depot, which is exactly what it sounds like: an orbital gas station.

Image Credits: Astroscale

Some other concepts of space refueling opt for the relative simplicity of keeping all fuel on the craft itself rather than acting as an emergency shuttle between the station and the client (hence the AAA comparison). But since the military seems to think that a giant, geostatic pressure vessel full of hydrazine is the safest option, Astroscale is doing just that. For all we know, there may be a standalone version for civilian use.

This joint project—basically a cost-effective mid-split—is still only in the “concept of operations” phase, but Astroscale expects to deliver it by 2026. No doubt we’ll be hearing more about this and other space viability projects soon. before then.