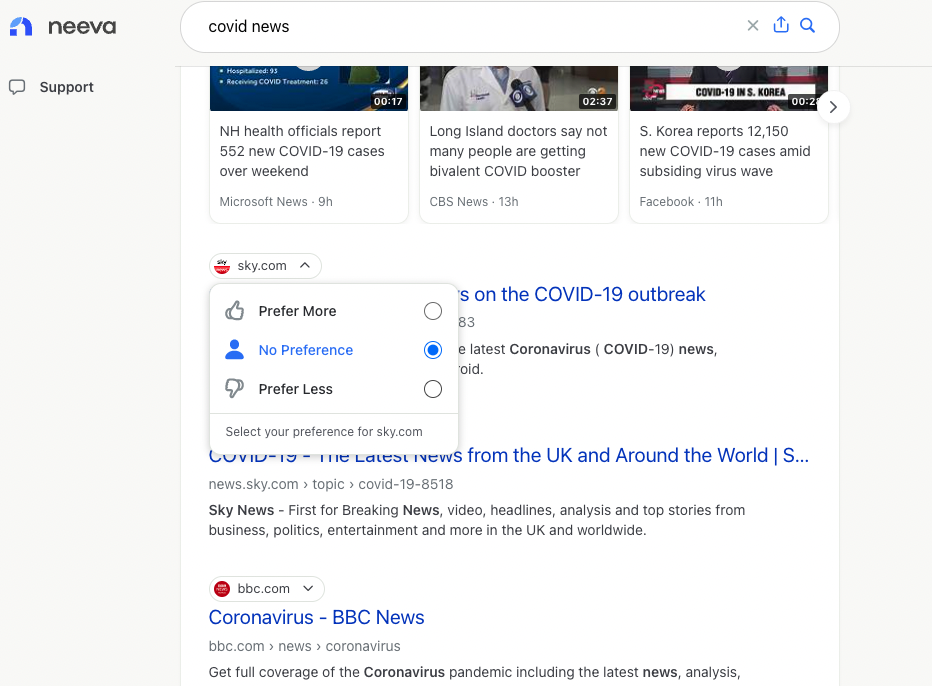

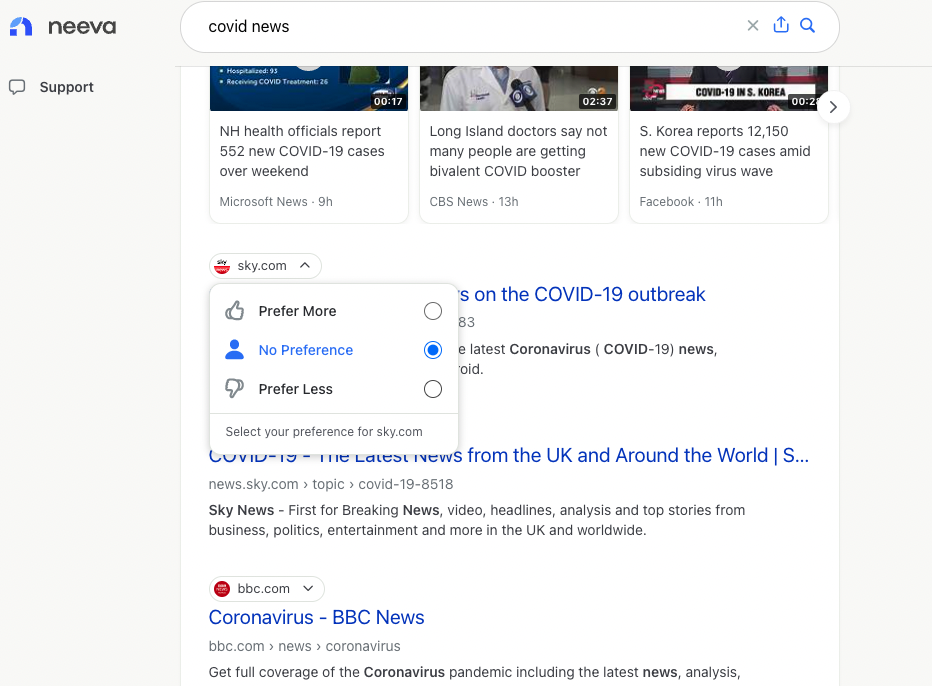

ONE court filing in the US Department of Justice’s case against Google over its alleged monopoly in the search market, revealed some remarkable facts about the state of competition in the search market, including internal operations, revenues and, in some cases, exit prices be Google competitors like DuckDuckGo and Neeva, the latter of which was sold to Snowflake last year after turning around the business.

Google’s proposed “Findings of Fact” filing documents the history of search competition, including Google’s own principles, innovations, the competitive landscape, Google’s search advertising business, distribution agreements, and more.

Of particular interest to us were the sections covering web search startups such as DuckDuckGo and Neeva and their business developments.

The filing reveals some details we already knew about DuckDuckGo — for example, that it has been profitable since 2014 and that its source Operating revenue is currently search adsspecifically search ads provided by Microsoft in the U.S. However, Google’s proposal also attempts to paint a picture of a startup that did not invest in search innovation, but focused on returning the investment to its shareholders.

As the filing claims, DuckDuckGo raised $10 million in 2018, but “the majority of that money was distributed to DuckDuckGo shareholders,” rather than being used to improve its search engine. When DuckDuckGo raised funds again in 2020 — a $100 million round — some of that went back to shareholders. (The exact percentage has been redacted.) When shareholders sold shares to various VC firms, those funds were not used to improve the search engine, the filing claims. But he contradicts that point, noting that a third of DuckDuckGo’s 50 employees in 2018 were working on improving the search engine, for example.

Image Credits: DuckDuckGo

However, the paper points out that despite DuckDuckGo’s profitability, it had not built its own “comprehensive web index” for organic search results – hardly a point in Google’s favor. Additionally, when Apple was asked if it would consider making DuckDuckGo the default in the Safari browser, Apple’s VP of Services, Eddy Cue, replied: “No, we haven’t . . . not a good choice for customers.” Ouch!

Also included is the scope of DuckDuckGo’s activities. The filing notes that the startup estimates its search engine was used by 100 million people worldwide by 2021. The search engine only receives about 2.5% of general search queries in the US, despite estimates that 10% of people in US claims to be users. That, DuckDuckGo’s leadership explained, is because people often use its search engine for some, but not all, of their search queries.

In Europe, DuckDuckGo received only 0.6% of mobile search queries as of August 2023, even after the introduction of the Android “selection screen” where it is offered as an option. Overall, the percentage of search queries in Europe ranged from 0.5% to 2.5% in 2023, depending on the country.

Image Credits: DuckDuckGo

By presenting these findings, Google hopes to prove that people choose its search engine because it is better and more innovative, not because of its monopoly share.

It also dismisses DuckDuckGo’s approach to privacy as one of its failings, arguing that the approach leads to “significant trade-offs in search quality,” by not using data like search sessions, a connected experience, and more. However, these details and others included in the filing show how difficult it is for a competitor to build a search business to compete with Google’s.

Another startup that serves as an example of this problem is Neeva, the search engine founded in 2019 by ex-Googlers Sridhar Ramaswamy and Vivek Raghunathan. Neeva initially seemed promising, not only because of her case, but also because of her founding team. CEO Ramaswamy worked at Google from 2003 to 2018 and held senior positions where he reported to the CEO and managed Google’s advertising, commerce, search infrastructure and privacy teams, the court filing reminds us.

With the team’s deep technical expertise and experience, they came up with a plan to offer consumers an ad-free alternative to Google, generating revenue through subscriptions. By 2022, Neeva said it had amassed more than 600,000 users, but most were not paying customers at the time.

Downgrade search results. Image Credits: Neva

The court filing offers a few more details about Neeva’s development, noting funding from top VC firms like Sequoia Capital and Greylock Ventures, in addition to Ramaswamy’s personal investment. The company believed it could successfully compete on search quality in the US and select other markets with just a 2.5% share of generic queries, Ramaswamy had testified during the trial.

The startup began by offering results through Microsoft’s Bing while developing its own search infrastructure. By 2022, it was using its own techniques to rank web results and believed it was comparable to Google and better than Bing thanks to the use of machine learning, natural language processing and other techniques.

To develop and train the machine learning models, it licensed anonymized information in the form of commercially available datasets. Google couldn’t claim that Neeva wasn’t innovating here. The startup last year released an artificial intelligence generation feature, Neeva AI, which is similar to what Google is now testing with Search Generative Experience (SGE), in that it also answers certain queries directly on search results pages using AI.

As a result, Neeva managed to attract some users. The filing notes that at its peak, it had “several million unique users per month,” Ramaswamy said. Unfortunately, its inability to compete with free search eventually led the startup to shut down its consumer operations, pivot to enterprise, and eventually exit Snowflake, as it was unable to attract the necessary venture capital funding to continue scaling operations. her.

“My co-founder, Vivek, and I came to the hesitant conclusion that we couldn’t build a business fast enough to be able to continue to raise capital to support the development of the product and the team,” Ramaswamy testified. “Well earlier this year, in May [2023] — we actually started talks about potential acquisitions in March — but earlier this year, in May, we closed the consumer search engine, returned the money customers had paid us, and acquired Snowflake, which is an enterprise data company.” he said.

Neeva was generating less than $1 million in subscription revenue at the time and growing, but it was still a small part of the search market, the filing also informs us.

The startup exited Snowflake for about $184.4 million in cash, more than double the amount it had invested, the filing said. This is slightly higher than previous reports that had adjusted the number 150 million dollars.

While not a startup, the document also touches on Yahoo’s (TechCrunch’s parent) lost search business, noting that it stopped crawling the web after a 2009 deal with Microsoft for algorithmic search and paid search ads. This partnership allowed Yahoo to reduce its investment in search and focus on other more popular products, such as Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports, Yahoo News and Yahoo Mail. (Much of the Yahoo section has been redacted, we should note.) He adds that Mozilla once had a deal with Yahoo but dropped it over search quality.

With few viable market competitors in the search space, Google is trying to argue that it competes with a number of other products, such as dedicated mobile apps and websites that offer some niche type of search, such as Yelp, Airbnb, Amazon, Expedia, Booking.com, Hotels.com and more. It also claims to compete with artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT, and social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest and TikTok — the latter three, particularly among younger users.

For example, Google VP of search Liz Reid said in 2021 that “63% of daily TikTok users aged 18 to 24 said they use[d] TikTok as a search engine in the last week.”

Whether or not the court will be swayed by Google’s argument that it is not a monopoly in search and search advertising more generally, which is a big part of this case, remains to be seen. Google is clearly the winner in the search market, but it’s not for lack of competitors trying to get in, as these examples show. But the trial had already revealed that Google used its considerable resources to maintain its position in the search market — for example, by paying Apple $18 billion to be the default search on iPhones. Meanwhile, Apple weighed in on Microsoft’s purchase of Bing in 2020 and had too thought of making DuckDuckGo the default engine in Safaribefore you dismiss the idea of continuing to cash Google checks.