Despite an overall decline in investment in startups, funding for artificial intelligence increased last year. Funds to productive AI firms alone nearly increased tenfold from 2022 to 2023, reaching $25.2 billion by the end of December.

So it’s no surprise that AI startups dominated Y Combinator’s Winter 2024 Demo Day.

The Y Combinator Winter 2024 cohort has 86 AI startups, according to YC’s official startup directory — nearly double the number from the Winter 2023 batch and nearly triple the number from Winter 2021. technology of the moment.

As we did last year, we went through Y Combinator’s newest cohort — the cohort that was introduced during this week’s Demo Day — and picked out some of the most interesting AI startups. Everyone made the cut for different reasons. But at a baseline, they stood out from the rest, whether it was for their technology, the addressable market, or the backgrounds of their founders.

Hazel

August Chen (exPalantir) and Elton Lossner (formerly of the Boston Consulting Group) assert that the government contracting process is hopelessly stalled.

Contracts are posted on thousands of different websites and can contain hundreds of pages of overlapping regulations. (The US federal government itself signs one is appreciated over 11 million contracts annually.) Responding to these offers can amount to entire business divisions, supported by outside consultants and law firms.

Chen and Lossner’s solution is artificial intelligence to automate the process of discovering, drafting and complying with government contracts. The couple – who met in college – are called Hazel.

Image Credits: Hazel

Using Hazel, users can match a potential contract, create a response plan based on the RFP and their company information, create a checklist of obligations, and automatically run compliance checks.

Given AI’s tendency to hallucinate, I’m a bit skeptical that the answers and checks Hazel generates will be consistently accurate. But if they’re even close, they could save a huge amount of time and effort, enabling smaller companies to handle the hundreds of billions of dollars worth of government contracts awarded each year.

Andy AI

Home nurses face a lot of paperwork. Tiantian Zha knows this well — she used to work at Verily, Google’s parent company Alphabetof life sciences, where he was involved in moonshots ranging from personalized medicine to reducing mosquito-borne diseases.

During her work, Zha discovered that documentation was an important time for home nurses. It’s a widespread issue — according to one studynurses spend over a third of their time on documentation, reducing the time they spend caring for patients and contributing to burnout.

To help ease the documentation burden for nurses, Zha co-founded Andy AI with Max Akhterov, ex apple staff engineer. Andy is essentially an AI scribe, recording and transcribing the verbal details of a patient visit and creating electronic health records.

Image Credits: Andy AI

As with any AI-powered transcription tool, it exists risk of bias — i.e. the tool doesn’t work well for some nurses and patients depending on pronunciations and word choices, and competitively Andy isn’t exactly the first of its kind on the market — competitors include DeepScribe, Heidi Health, Nabla and Amazon HealthScribe’s AWS.

But as health care more and more is shifting to the home, demand for apps like Andy AI looks poised to grow.

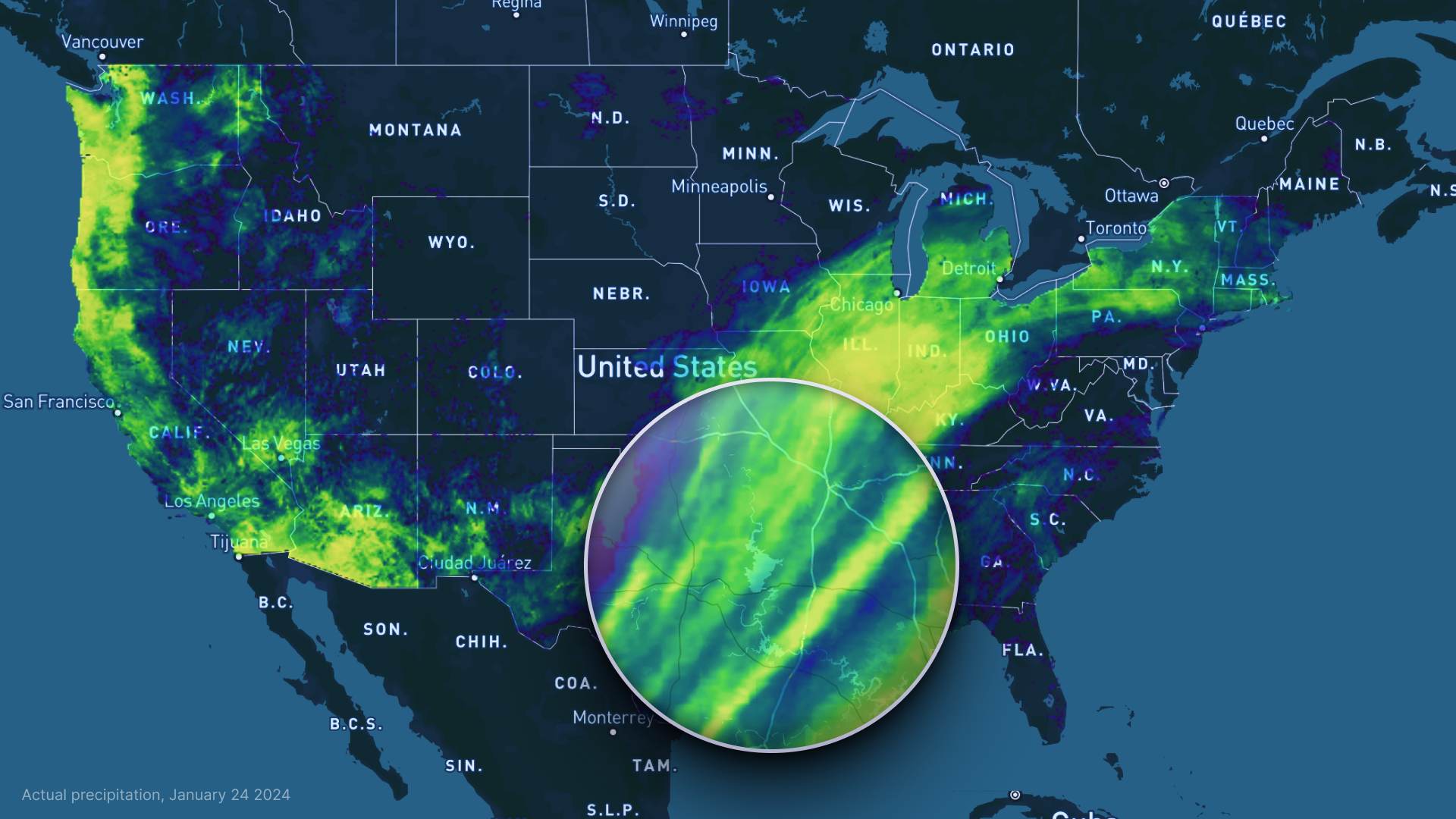

Precipitation

If your experience with weather apps is anything like this reporter’s, you’ve been caught in a storm after blindly believing the forecast of blue skies.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

At least, that’s the premise of Precip, an AI-powered weather forecasting platform. Jesse Vollmar had the idea after founding FarmLogs, a startup that sold crop management software. He teamed up with Sam Pierce Lolla and Michael Asher, previously Chief Data Scientist at FarmLogs, to make Precipitation a reality.

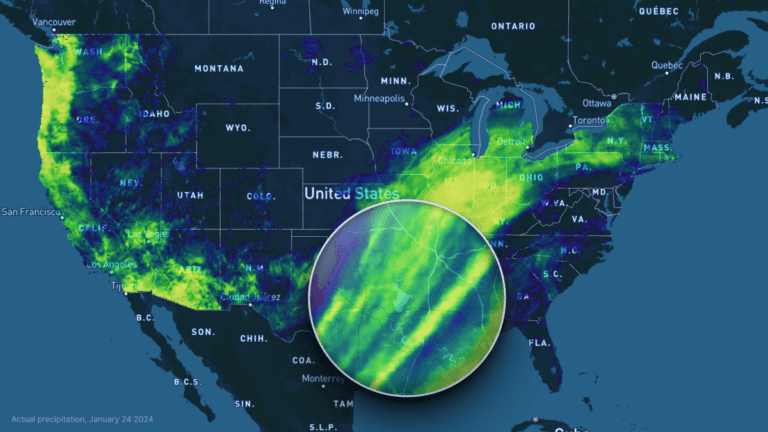

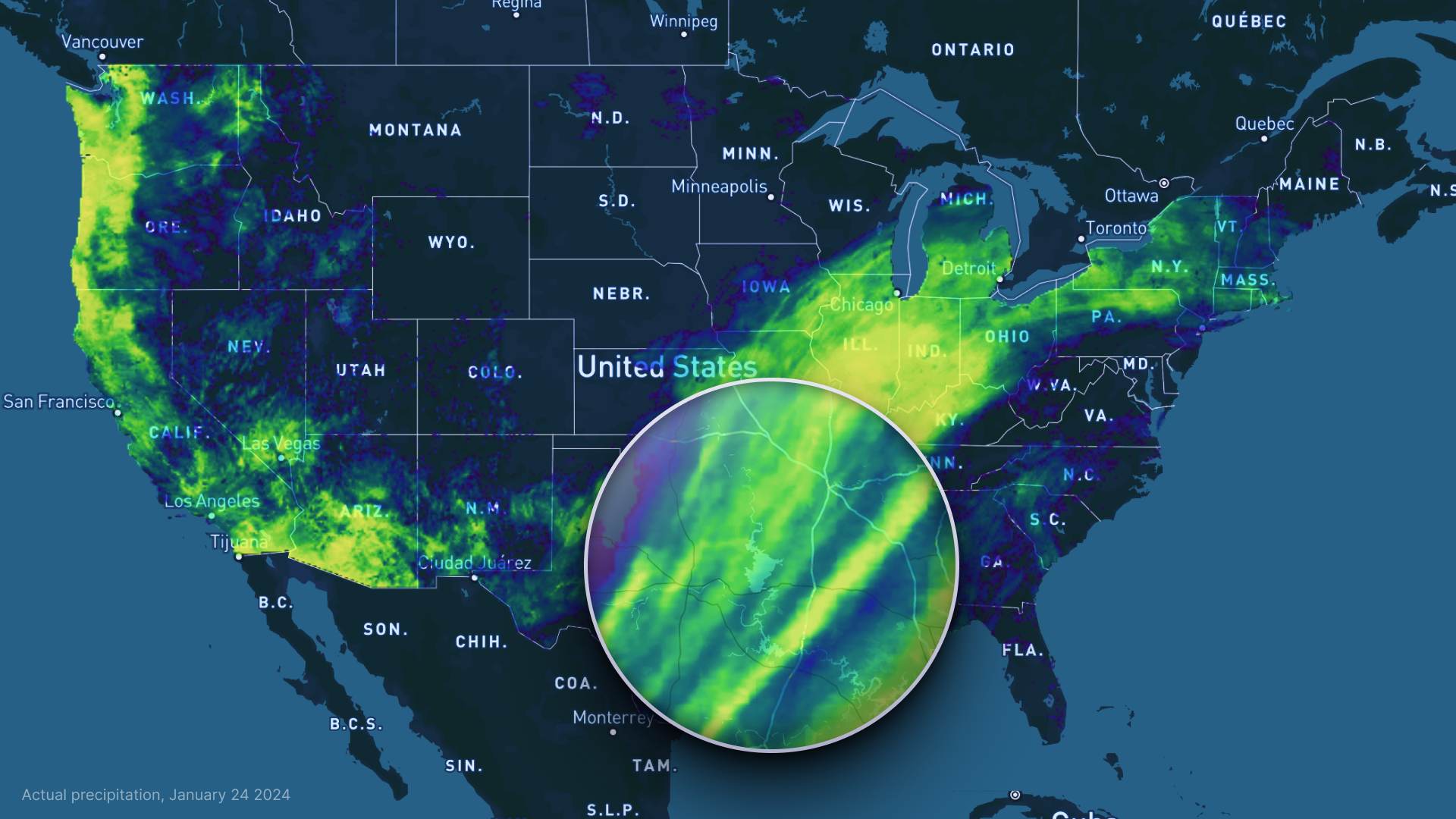

Image Credits: Precipitation

Precip provides detailed information on precipitation, for example by calculating the amount of precipitation in a given geographic area over the past several hours to days. Vollmar claims Precip can generate “high precision” readings for any location in the US down to a kilometer (or two), predicting conditions up to seven days ahead.

So what is the value of rainfall measurements and alerts? Well, Vollmar says farmers can use them to track crop growth, construction crews can report them to schedule crews, and utilities can use them to predict service interruptions. A transportation customer checks Precip daily to avoid bad driving conditions, Vollmar claims.

Of course, there is no shortage of weather forecasting apps. But AI like Precip promises to make predictions more accurate — if AI is really worth it.

Midwife

Claire Wiley started a couples coaching program while studying for her MBA at Wharton. The experience led her to explore a more technological approach to relationships and therapy, which resulted in Midwife.

Maia — which Wiley co-founded with Ralph Ma, a former Google Research scientist — aims to empower couples to build stronger relationships through artificial intelligence guidance. In Maia’s Android and iOS apps, couples message each other in a group chat and answer daily questions like what they see as challenges they need to overcome, pain points they’ve worked through, and lists of things they’re grateful for.

Image Credits: Midwife

Maia plans to make money by charging for premium features like therapist-created programs and unlimited messaging. (Maia usually shuts down texts between partners—a frustratingly arbitrary restriction if you ask me, but it’s true.)

Wiley and Ma, who both come from divorced households, say they worked with a relationship specialist to create Maia’s experience. The questions on my mind, however, are (1) how sound is Maia’s relationship science, and (2) can it stand out in the extremely crowded field of dating apps? We’ll have to wait and see.

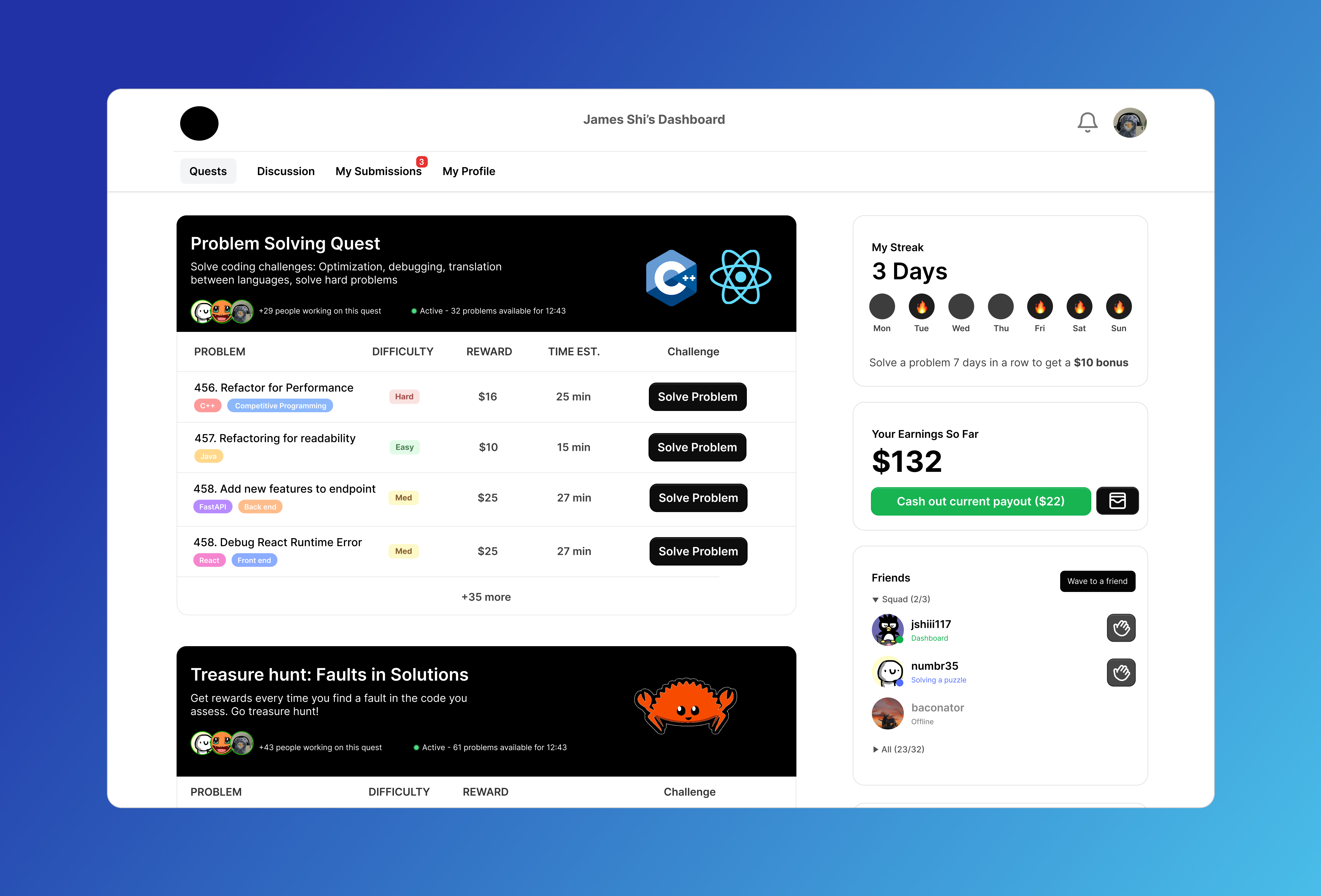

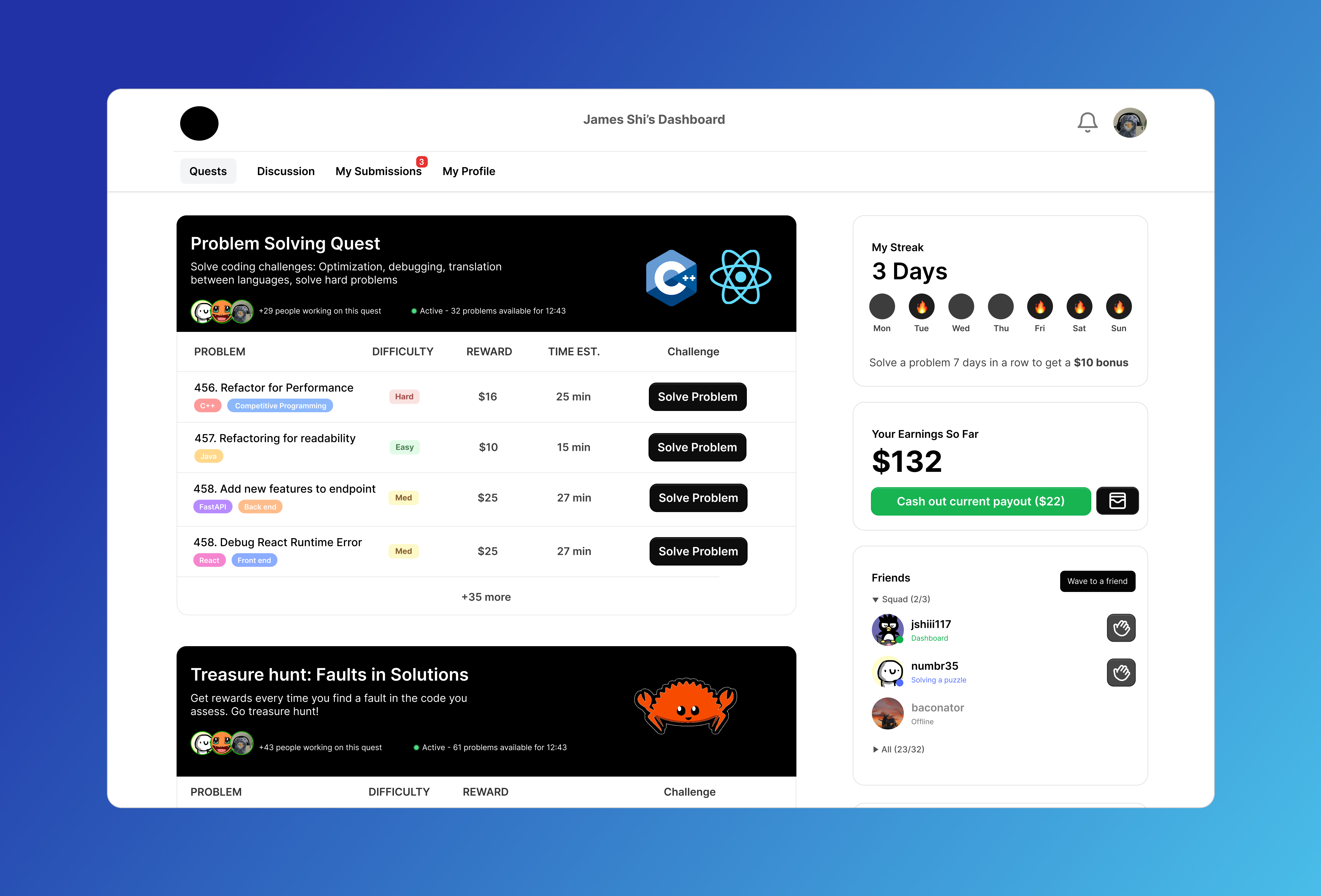

Data curve

The AI models at the heart of productive AI applications like ChatGPT are trained on massive datasets, combinations of public and proprietary data from across the web, including e-books, social media posts, and personal blogs. But some of that data is legally and ethically problematic—not to mention flawed but ways.

A clear lack of data curation is the problem, if you ask Serena Ge and Charley Lee.

Ge and Lee co-founded Data curve, which provides “special quality” data for training artificial intelligence models that are created. It’s code-specific data, which Ge and Lee say is particularly difficult to obtain thanks to the expertise required to label it for AI training and restrictive licenses.

Image Credits: Data curve

Datacurve hosts a gamified annotation platform that pays engineers to solve coding challenges, which contributes to Datacurve’s educational datasets for sale. These datasets, speaking of, can be used to train models for code optimization, code generation, debugging, user interface design, and more, Ge and Lee say.

It’s an interesting idea to be sure. But Datacurve’s success will depend on how well-curated its datasets are — and whether it can incentivize enough developers to keep developing and improving them.