AIs are easy playing the SAT, beating chess grandmasters, and debugging code like it’s nothing. But put an AI up against some middle schoolers in spelling, and it’ll be dismissed faster than you can say diffusion.

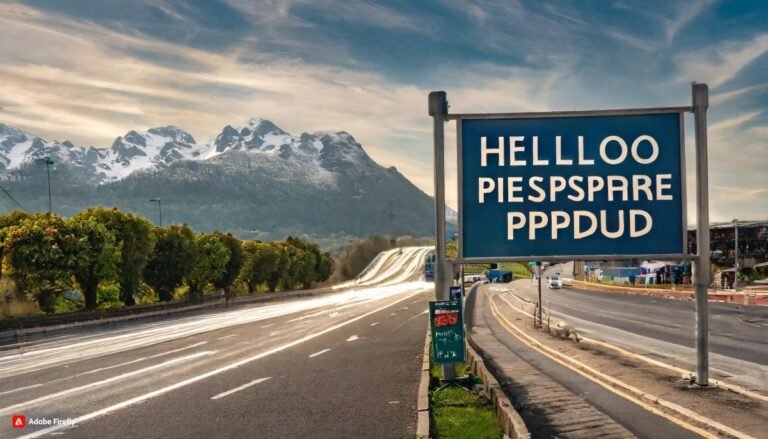

Despite all the advances we’ve seen in AI, it still can’t write. If you ask text-to-image generators like DALL-E to create a menu for a Mexican restaurant, you might spot some appetizing items like “taao,” “burto,” and “enchida” among a sea of other gibberish.

And while ChatGPT might be able to write your papers for you, it’s comically inept when you ask it to find a 10-letter word without the letters “A” or “E” (it told me “balaclava”). Meanwhile, when a friend tried to use Instagram’s AI to create a sticker that said “new post,” it produced a graphic that appeared to say something we weren’t allowed to repeat on TechCrunch, a family-friendly website.

Image Credits: Microsoft Designer (DALL-E 3)

“Image generators tend to perform much better on objects like cars and people’s faces, and less so on smaller things like fingers and handwriting,” said Asmelash Teka Hadgu, co-founder of Lesan and a partner in DAIR Institute.

The underlying technology behind image and text generators is different, but both kinds of models have similar problems with details like spelling. Image generators generally use diffusion models, which reconstruct an image from noise. When it comes to text generators, large language models (LLMs) may seem like they read and respond to your prompts like a human brain — but they actually use complex math to match the prompt pattern with one in its latent space. letting it continue the pattern with a response.

“Diffusion models, the newest kind of algorithms used to generate images, reconstruct a given input,” Hagdu told TechCrunch. “We can assume that the writing in an image is a very, very tiny part, so the image generator learns the patterns that cover more than those pixels.”

Algorithms are motivated to recreate something that looks like what’s seen in the training data, but it doesn’t inherently know the rules we take for granted—that “hello” isn’t spelled “heeeelllooo” and that human hands typically have five fingers.

“Even just last year, all these models were really bad at fingers, and that’s exactly the same problem with text,” said Matthew Guzdial, an artificial intelligence researcher and assistant professor at the University of Alberta. “They’re getting really good at it locally, so if you look at a hand with six or seven fingers on it, you might say, ‘Oh, wow, that looks like a finger.’ Likewise, with the generated text, you could say, it looks like an ‘H’ and it looks like a ‘P,’ but it’s really bad at structuring all those things together.”

Engineers can improve these issues by augmenting their datasets with training models specifically designed to teach AI what hands should look like. But experts don’t predict these spelling issues will be resolved so quickly.

Image Credits: Adobe Firefly

“You can imagine doing something similar – if we just generate a whole bunch of text, they can train a model to try to identify what’s good versus bad, and that might improve things a bit. But unfortunately, the English language is very complicated,” Guzdial told TechCrunch. And the issue gets even more complicated when you consider how many different languages AI has to learn to work with.

Some models, such as Adobe Firefly, are taught not to generate text at all. If you enter something simple like “menu in a restaurant” or “billboard with advertisement” you will get an image of a white paper on a dinner table or a white billboard on the highway. But if you put enough detail into your prompt, these guardrails are easy to bypass.

“You can think of it almost like they’re playing Whac-A-Mole, like, ‘OK, a lot of people are complaining about our hands — we’re going to add a new thing that’s just for the hands in the next model,’ and so on and so forth,” he said. Guzdial. “But text is much more difficult. Because of that, even ChatGPT can’t really spell.”

On Reddit, YouTube, and X, a few people have uploaded videos showing how ChatGPT fails at spelling ASCII art, an early internet art form that uses text characters to create images. In a recent video, which was called “an instant mechanical hero’s journey,” someone is trying hard to guide ChatGPT by creating ASCII art that says “Honda.” They succeed in the end, but not without Odyssean trials and tribulations.

“One hypothesis I have there is that they didn’t have a lot of ASCII art in their training,” Hagdu said. “That’s the simplest explanation.”

But basically, LLMs just don’t understand what letters are, even if they can write sonnets in seconds.

“LLMs are based on this transformer architecture, which mostly doesn’t read text. What happens when you enter a prompt is that it translates into an encoding,” Guzdial said. “When he sees the word ‘the’, he has this encoding of what ‘the’ means, but he doesn’t know about ‘T’, ‘H’, ‘E’.

That’s why when you ask ChatGPT to generate a list of eight-letter words without an “O” or an “S,” it gets it wrong about half the time. He doesn’t actually know what “O” or “S” is (though he could probably give you the history of the letter on Wikipedia).

While those DALL-E pictures of bad restaurant menus are funny, AI’s shortcomings are useful when it comes to spotting misinformation. When trying to see if a questionable image is real or AI-generated, we can learn a lot by looking at signs, T-shirts with text, book pages, or anything else where a series of random letters can give away the synthetic image of an image. origin. And before these models get better at making hands, a sixth (or seventh or eighth) finger could be a giveaway, too.

But, says Guzdial, if we look closely enough, it’s not just fingers and spelling that AI gets wrong.

“These models are constantly creating these small, localized issues — we’re just particularly well-tuned to recognize some of them,” he said.

Image Credits: Adobe Firefly

For an average person, for example, an AI-generated image of a music store could be easily believable. But someone who knows little about music might look at the same picture and notice that some of the guitars have seven strings, or that the black and white keys on a piano are the wrong distance apart.

Although these AI models are improving at an alarming rate, these tools still face problems like this, which limit the capacity of the technology.

“This is concrete progress, there’s no doubt about it,” Hagdu said. “But the kind of hype this technology is generating is just crazy.”