ChatGPT, OpenAI’s viral AI chatbot, turns one year old today.

A year ago, OpenAI launched ChatGPT as a “low-key research preview” — reportedly partly motivated by intense competition with AI startup Anthropic. The goal, OpenAI leadership he said OpenAI’s ranking at the time was to collect more data about how people use and interact with genetic AI to inform the development of future OpenAI models.

Originally a basic, free-to-use, web-based and chat-focused interface on top of one of OpenAI’s existing models, GPT-3.5, ChatGPT would go on to become the company’s most popular product… ever — and the The fastest growing consumer app in history.

In the months following its launch, ChatGPT gained paid tiers with additional features, including a plan aimed at enterprise customers. OpenAI also upgraded ChatGPT with web search, document analysis and image generation capabilities (via DALL-E 3). And, relying on in-house developed speech recognition, voice synthesis and text-image understanding models, OpenAI enabled ChatGPT to “hear”, “speak”, “see” and take actions.

Indeed, ChatGPT became the number one priority at OpenAI — not just a single-use product, but a development platform to leverage. And, as is often the case in a competition-driven market, it shifted focus to other AI companies and research labs.

Google tried to launch an answer to ChatGPT, finally releasing Bard, a more or less comparable AI chatbot, in February. Countless other ChatGPT competitors and derivatives have hit the market since, most recently Amazon Q, a more business-like approach to ChatGPT. DeepMind, Google’s flagship artificial intelligence research lab, is expected to debut its next-generation chatbot, Gemini, before the end of the year.

Stella Biderman, an AI researcher at Booz Allen Hamilton and the open research group EleutherAI, told me she doesn’t see ChatGPT as an AI breakthrough in itself. (OpenAI, which has released dozens of research papers on its models, has never released any on ChatGPT). But, he says, ChatGPT was a good “user experience breakthrough” — taking AI mainstream.

“The primary impact [ChatGPT] he had [is] encouraging people who train AI to try to emulate it, or encouraging people who study AI to use it as a central object of study,” Biderman said. “Previously you needed to have some skill, even if you weren’t an expert, to constantly get useful things out of [text-generating models]. Now that this has changed… [ChatGPT has] brought a lot of attention and discussion to the technology.”

And ChatGPT is still getting a lot of attention — at least if third-party statistics are anything to go by.

Image Credits: CFOTO/Future Publishing/Getty Images

According to Web metrics company Similarweb, OpenAI’s ChatGPT web portal saw 140.7 million unique visitors in October, while the ChatGPT apps for iOS and Android have 4.9 million monthly active users in the US alone. Data from analytics firm Data.ai suggests the apps have generated nearly $30 million in subscription revenue — a huge amount considering they only launched a few months ago.

One of the reasons for ChatGTP’s enduring popularity is its ability to conduct conversations that are “convincingly real,” according to Ruoxi Shang, a third-year Ph.D. student at the University of Washington studying human-AI interaction. Before ChatGPT, people were already familiar with chatbots — they’ve been around for decades after all. But the models powering ChatGPT are much more sophisticated than what many users are used to.

“Human-computer interaction researchers have studied how conversational interfaces can improve information comprehension, and the socialization aspects of chatbots bring increased engagement,” Shang said. “Now, artificial intelligence models have enabled interlocutors to conduct conversations that are almost indistinguishable from human dialogues.”

Adam Hyland, also a Ph.D. student studying artificial intelligence at the University of Washington, points out the emotional component: conversations with ChatGPT have a noticeably different “feel” than with more rudimentary chatbots.

“In the 1960s, ELIZA offered a chatbot whose response was very similar to how people responded to ChatGPT,” Hyland said, referring to the chatbot created by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum in 1966. “The people interacting with the system inferred emotional content and a linear narrative in chat messages.”

Indeed, ChatGPT has impressed cynics like Kevin Roose of the New York Times, who called is “the best AI chatbot ever released to the general public”. In The Atlantic Magazine’s Breakthroughs of the Year for 2022, Derek Thompson included ChatGPT as part of the “birth AI explosion” that “may change our minds about how we work, how we think and what human creativity is.”

ChatGPT’s skills extend beyond chat, of course—another possible reason for his stay. ChatGPT can complete and proofread code, compose music and essays, answer test questions, generate business ideas, write poetry and song lyrics, translate and summarize text, and more emulate a Linux computer.

An MIT study showed that, for tasks such as writing cover letters, “thin” emails and cost-benefit analyses, ChatGPT reduced the time it took workers to complete tasks by 40%, while increasing production quality by 18%; as measured by third-party evaluators.

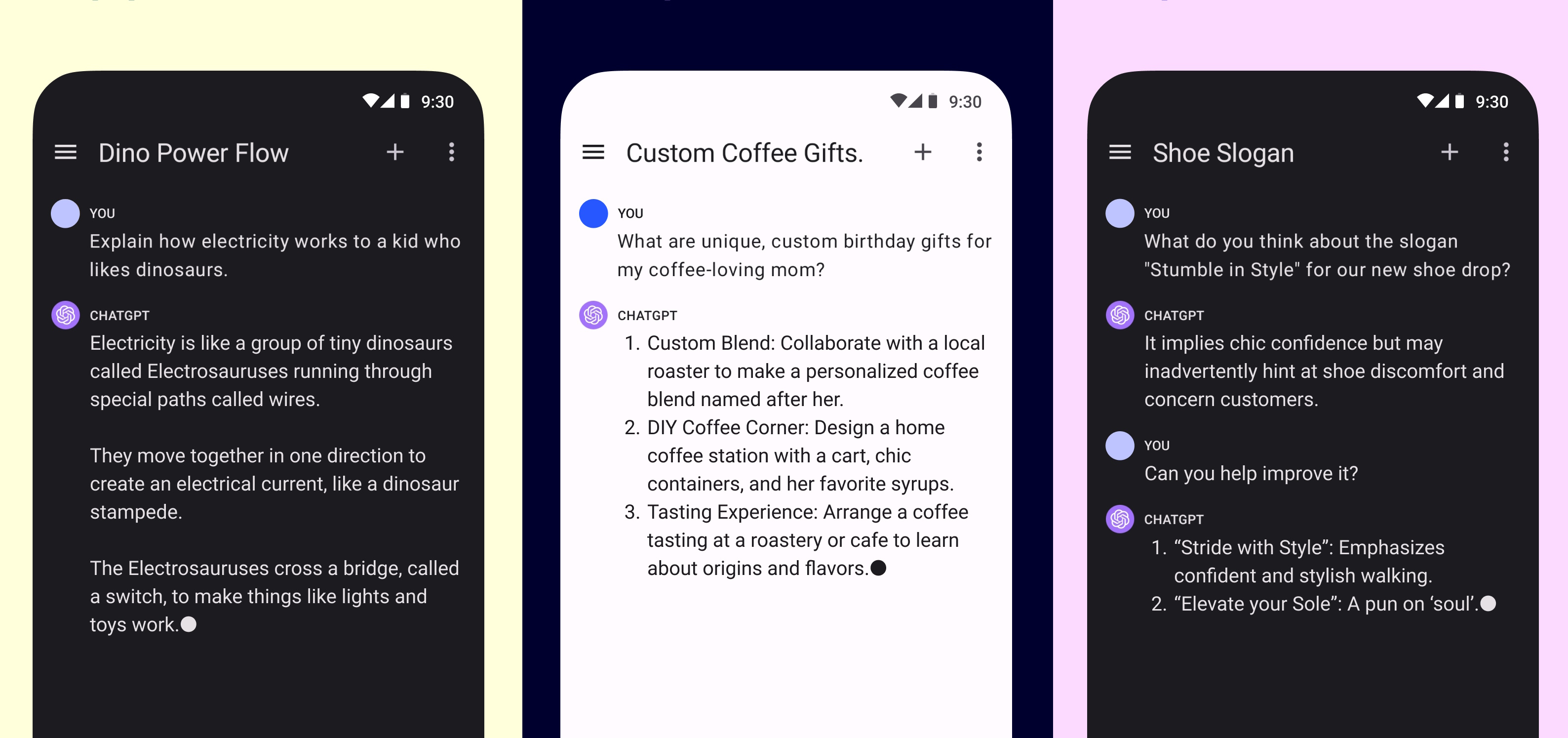

ChatGPT screens and prompt examples from the Android app, which was released in July.

“Because [the AI models powering OpenAI] have been extensively trained on massive amounts of data,” Shang added, “they [have] shifted focus from training specialized chatbots for specific domains to building more general-purpose systems that can handle a variety of topics easily through prompting with instructions… [Chatbots like ChatGPT] don’t require users to learn any new form of language, as long as they provide a task and some desired outcomes just as a manager would communicate to an intern.”

Now, there is mixed evidence as to whether ChatGPT is actually being used in these ways. A Pew Research survey in August found that only 18% of Americans have ever tried ChatGPT, and that most who have tried it use the chatbot for entertainment purposes or to answer individual questions. Teenagers may not be using ChatGPT so often, either (despite the titles of some alarms entail), with one poll finding that only two in five teens have used technology in the past six months.

ChatGPT limitations may be to blame.

While undeniably capable, ChatGPT is far from perfect due to the way it was developed and “taught”. Trained to predict the most likely next word — or like the next parts of words — by observing billions of examples of text from around the web, ChatGPT sometimes “hallucinates,” or writes answers that sound reasonable, but is not really right. (ChatGPT’s hallucinatory tendencies got his answers banned from the Q&A site Stack Overflow and from at least one academic conference — and is accused of defamation.) ChatGPT can also show bias in its responses by responding sexist and racistovertly Anglocentric ways — or reverting parts of the data it was trained on.

Lawyers have been sanctioned after using ChatGPT to help draft sentences, only to discover—too late—that ChatGPT fabricated false lawsuit reports. And ratings of authors have sued OpenAI over the chatbot that degraded parts of their work – and received no compensation for it.

So what’s next? What might the second year of ChatGPT include, if not more of the same?

Interestingly – and fortunately – some of the most dire predictions about ChatGPT did not come true. Some researchers feared that the chatbot would be used to create disinformation on a mass scale, while others raised the alarm about ChatGTP’s potential to generate email, spam, and malware.

The concerns pushed policymakers in Europe to mandate safety assessments for any products using AI systems like ChatGPT and over 20,000 signatories – including Elon Musk and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak – to sign an open letter calling for an immediate halt to experiments large-scale artificial intelligence such as ChatGPT.

But there have been examples of ChatGPT abuse in the wild few and away between – so far.

With the launch of GPTs, OpenAI’s tool for building custom AI systems with conversation and action powered by OpenAI models, including models that support ChatGPT, ChatGPT could become more of a gateway to a wider chatbot ecosystem with artificial intelligence from the end of everything – it’s everything.

The OpenAI logo on a smartphone screen in front of a laptop with the ChatGPT logo.

With GTPs, a user can train a model on a collection of cookbooks, for example, so that it can answer questions about the ingredients for a particular recipe. Or they can model their company’s proprietary codebases so that developers can control their style or build code according to best practices.

Some of the initial GPTs—all created by OpenAI—include a Gen Z meme translator, a coloring book and sticker maker, a data visualizer, a board game explainer, and a creative writing instructor. Now, ChatGPT can complete these tasks with carefully designed instructions and prior knowledge. But custom-built GTPs simplify things drastically — and might just kill the cottage industry that sprung up around creating and editing ChatGPT feed prompts.

GPTs introduce a level of personalization far beyond what ChatGPT currently offers, and — once OpenAI sorts out its capacity issues — I expect we’ll see an explosion of creativity there. Will ChatGPT be as visible as it once was after GPTs flood the market? Maybe not. But it won’t go away — it’ll just adapt and evolve, no doubt in ways that even its creators can’t predict.