Satellite imagery and machine learning offer a new, much more detailed look at the shipping industry, especially the number and activities of fishing and transport vessels at sea. Turns out there are way more than publicly available data would suggest, a fact that policymakers need to take note of.

As a shared global resource, the oceans are everyone’s business, but of course not every country or region has the same customs, laws or even motivations.

There is the Automated Identification System (AIS) that is increasingly being adopted around the world that uses ship transponders to accurately track activity, but it is not universally implemented. As a result, important data such as how many boats fish in an area, who operates them and how many fish they catch are often unclear, a patchwork of local, privately owned and government-sanctioned numbers.

Not only does this make political decisions difficult and approachable, but there is a sense of lawlessness in the industry, with countless vessels clandestinely visiting restricted or protected waters or wildly exceeding safe harvest numbers to quickly deplete stocks.

Satellite images offer a new perspective on this conundrum: you can’t hide from an eye in the sky. But the scale of the industry and the images that document it are huge. Fortunately, machine learning is here to perform the millions of vessel identification and tracking functions necessary to accurately track the tens of thousands of ships at sea at any given time.

In a paper published in NatureFernando Paolo, David Kroodsma, and their team at World Fishing Watch (with collaborators at several universities) analyzed two petabytes of orbital imagery from 2017-2021, locating millions of ships at sea and cross-referencing them with reported and known coordinates for AIS-tracked ships.

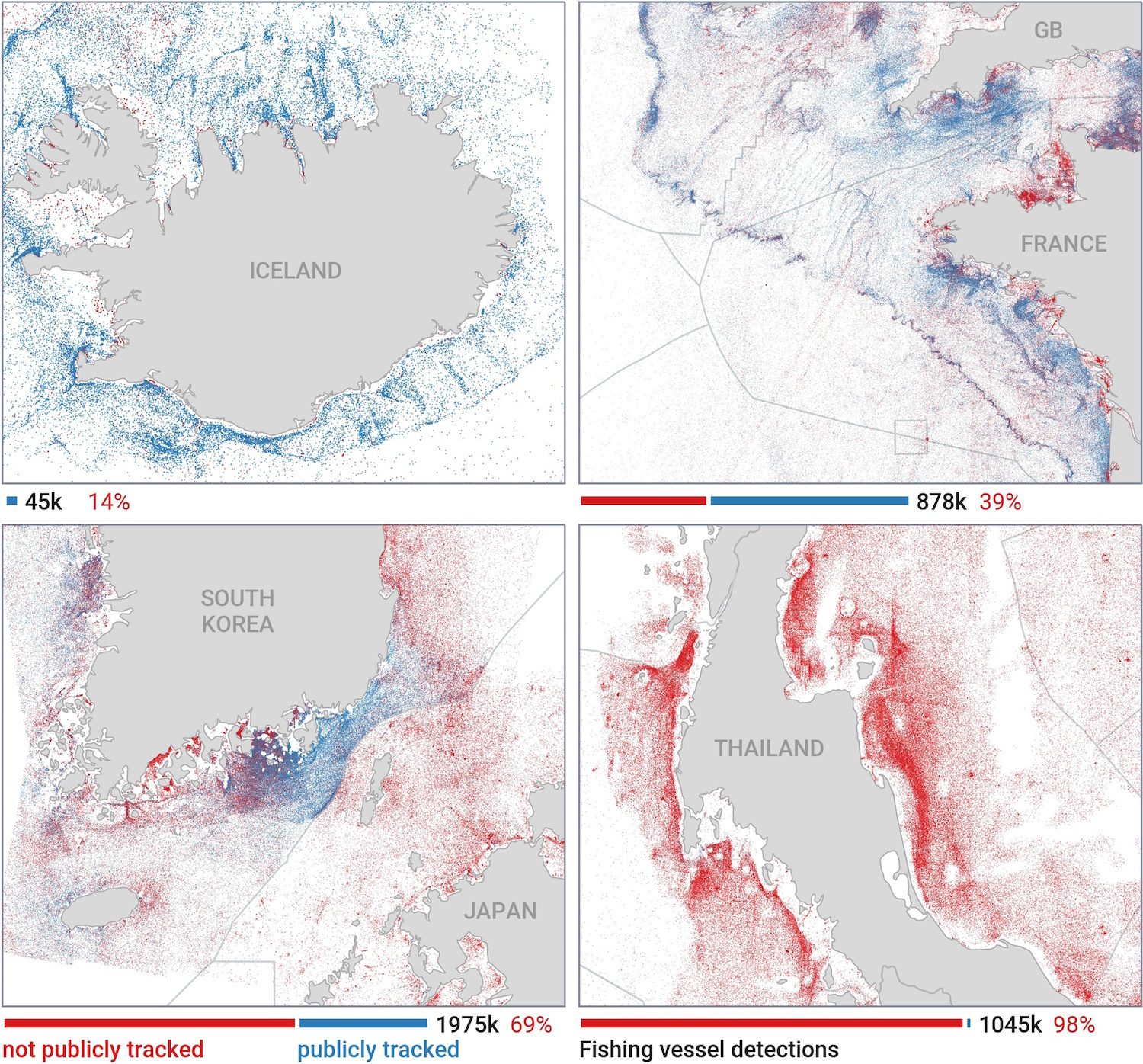

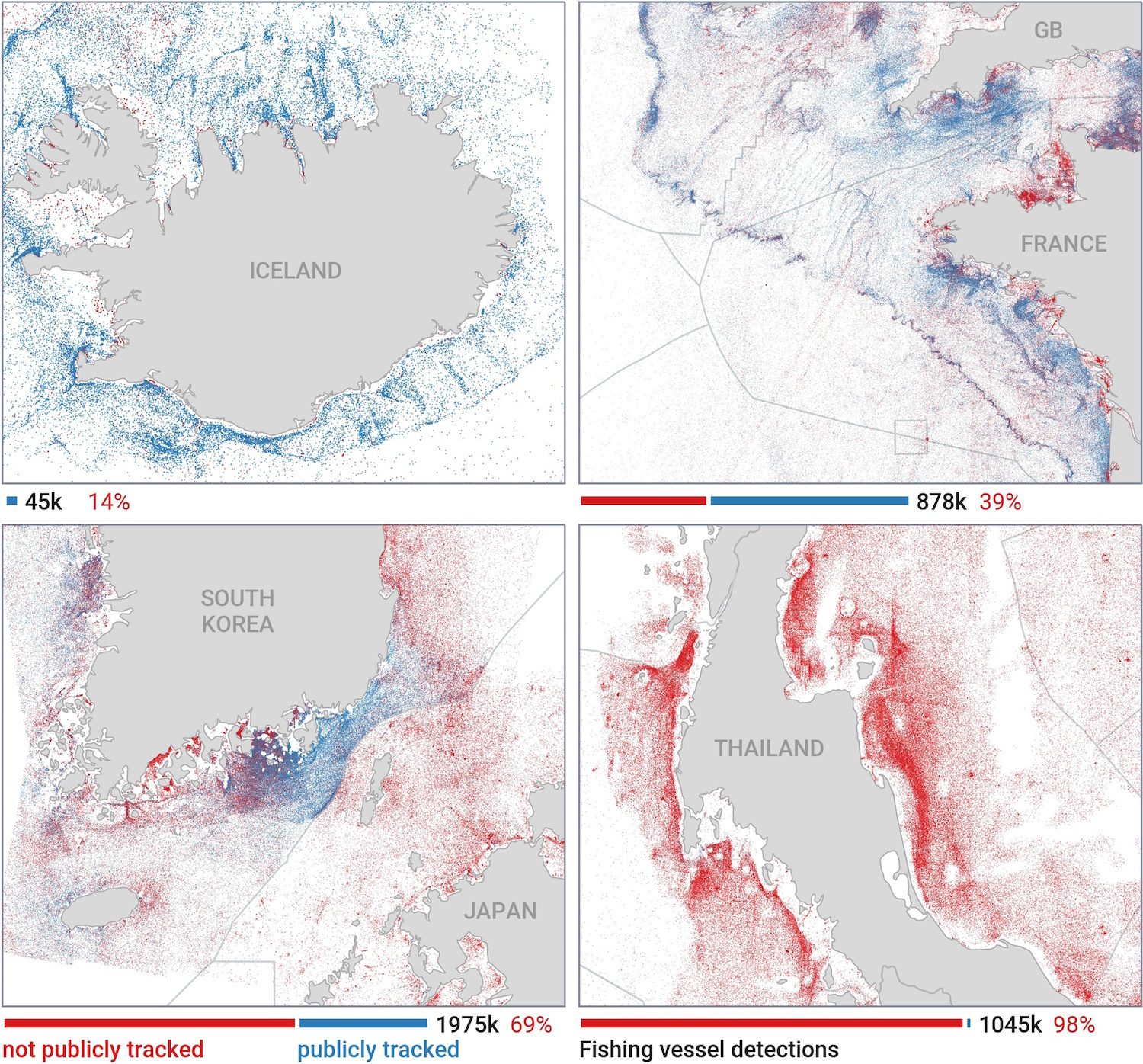

What the study documents is that about 3/4 of all industrial fishing vessels are not publicly monitored, and similarly almost a third of all transport and energy vessels. The dark fishing industry is huge — perhaps as big again as the publicly documented one. (The images also measured increases in installations of wind turbines and other renewable energy sources, which can be just as difficult to detect.)

Now, “not publicly tracked” doesn’t mean there’s no clue.

“There are a few reasons why these ships are missing from public tracking systems,” Paolo explained to TechCrunch. For example, smaller vessels and those operating in areas with little or no satellite coverage or AIS infrastructure are not tracked to the same extent as those that deliberately disable their transponders or evade detection.

“It is important to note that some countries have other (proprietary) means of tracking vessels within their own waters. But these proprietary systems are limited to the ships they can track and this information is not shared with other nations,” he continued.

As the population grows and the oceans warm, it is increasingly important that data like this is known beyond a nation’s borders and internal agencies.

“Fish are an important dynamic resource in circulation, so open monitoring of fishing vessels is fundamental to monitoring fish stocks. It is difficult to understand and map the full ecological footprint of vessels without all of them publicly broadcasting their locations and activity,” said Paolo.

Image Credits: World Fishing Watch

You can see in the illustrations that Iceland and Scandinavia have the highest levels of monitoring, while Southeast Asia has the lowest – almost zero on the coasts of Bangladesh, India and Myanmar.

As noted above, this does not mean that they are all illegal, just that their activity is not common, as legally required in Scandinavia. How much fishing is done from these areas? The global community only hears second-hand, and one of the study’s findings was that the Asian fishing industry is systematically underrepresented.

If you counted against the AIS data, you would find that about 36% of the fishing activity was in European waters and 44% in Asia. However, satellite data completely contradicts this, showing that only 10% of fishing vessels are in European waters and a staggering 71% in Asian waters. In fact, China alone seems to account for about 30% of all the fisheries on the planet!

Image Credits: World Fishing Watch

This is not meant to blame or blame these countries or regions, but simply to point out that our understanding of the scale of the global fishing industry is flawed. And if we don’t have good information to base our policies and science on, both will end up being fundamentally flawed.

That said, the satellite analysis also showed the regular presence of fishing vessels in protected areas such as the Galapagos Islands, which is strictly prohibited by international law. You can bet those dark vessels got a little extra attention.

“The next step is to work with authorities in different regions to evaluate these new maps. In some cases, we likely found some fishing in marine protected areas or restricted areas that will require further research and protection,” said Paolo.

He hopes the improved data will help guide policy, but the aggregation and analysis is far from complete.

“This is only the first version of our open data platform,” he said. “We are processing new radar images from the Sentinel-1 satellite as they are collected and tracking activity around the world. This data is visible and accessible on our website, globalfishingwatch.org, and is updated three days ago.

The non-profit organization is supported by a number of charities and individuals, which you can find here.