The prisoner’s dilemma is a classic thought experiment that explores how people can cooperate for mutual gain—or how one might harm another for a lesser reward.

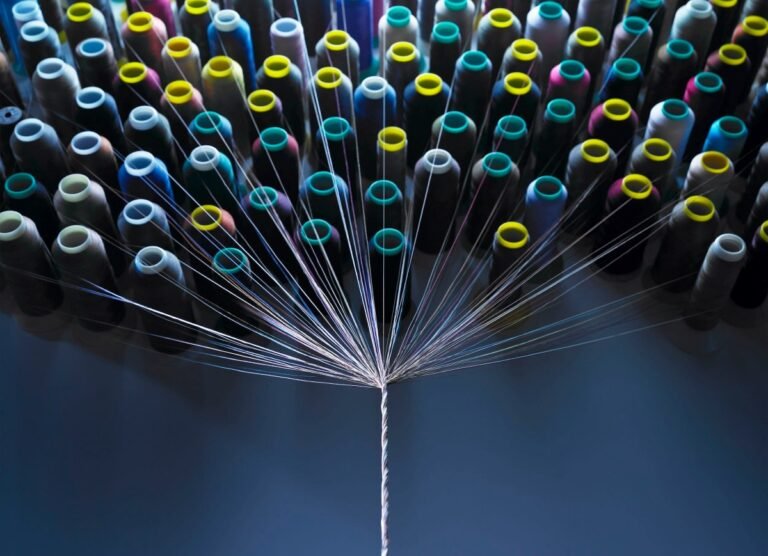

Can you guess what venture capital might look like? A group of Boston investors wishes it were otherwise.

This week, a group of five venture capitalists and the head of a real estate consultancy launched Venx (or venX), a collaborative group focused on deep technology investments. The five investors come from four different firms — Anzu Partners, Hitachi Ventures, Myriad Venture Partners and SkyRiver Ventures — and are still making individual decisions about when to write a check. But it could be the start of something bigger.

“The need for deep tech investment partnerships and the need to work together seemed obvious,” Hyuk-Jeen Suh told TechCrunch.

Suh, a general partner at SkyRiver, was inspired by startup accelerators like Greentown Labs in the Boston area, which started with a handful of climate tech founders and has grown into one of the world’s largest deep-tech incubators. Initially, Greentown’s founders were looking for lab space, but quickly realized that the benefits of shared space far outweighed lower rent payments.

“If you look at the startup ecosystem, they’ve realized that collaboration is better. There are economies of scale,” Suh said. Additionally, such incubators and other shared spaces can serve as a one-stop shop for investors looking for startups.

Until now, venture capital has lacked something similar. Yes, there’s Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley, but Suh felt the street looked more like a collection of car dealerships along a “car mile” than anything like a co-op group. “Everyone is competing. I felt there had to be a different way.”

Part of what allowed Venx to merge, Suh said, was that the four companies run the gamut of investment stages, from pre-seed to later stages, and represent a range of interests in deep technology, including climate technology , artificial intelligence and biotechnology. .

The fact that cooperation has emerged between deep-tech investors is not surprising. The kind of problems faced by deep-tech startups favor collaboration over extreme competition. They tend to require large pools of capital, expensive laboratory equipment and other expensive infrastructure. The problems they try to tackle often send them into uncharted territory. And the solutions they arrive at tend to benefit from diversity of thought.

For investors, there’s so much blue sky in deep tech that Suh doesn’t think secrecy and jealousy give anyone an advantage. “Why do VCs feel they have to compete? Don’t we have enough carbon to remove? Plastics for recycling or disposal? Breast cancer for treatment? Aren’t there enough challenges in AI?” Shared knowledge and access to deals will also benefit LPs, Suh said.

If this sounds like a union, it is – sort of.

Like syndicates, the group shares leads and each investor brings their own perspective and expertise to a meeting. But unlike unions, which at the venture stage tend to be informal and ad hoc, Venx is a more formal arrangement with the kind of intimacy that only shared space can offer.

For now, Venx consists of an office space where partners sit, rub elbows and chat over lunch. There is a meeting room where they can hear collective messages from the founders, after which they gather to share their thoughts. The group is open to new members since the majority of their investments are directly in startups (not other funds).

It’s easy to imagine Venx transforming into something more. More partners, more funds, maybe a common fund from which the team can write checks, similar to an angel syndicate. Whatever it ends up being, Venx’s collaborative approach is an interesting experiment worth watching.